It’s been ten years since I nearly died serving my country.

I sometimes think about all the things that have happened since that day: the sights I’ve seen, places I’ve lived, people I’ve met. Mountains summited, stages taken, and triumphs had. And of course, every moment spent with my wonderful wife-to-be, with whom falling in love has been a revelation. When I frame all of that lived life within the context of near-death, all of those experiences seem entirely optional.

Those experiences happened because I happened to be there, and I very easily could have not been. If I stare off into space and focus my eyes hard enough, I can just barely make out the shimmering mirage of that other reality where I never made it off that hospital bed. That universe is a different place, no doubt. But I cannot help but wonder how different that other universe really is, and how much that difference actually matters.

You can imagine why this is a weird topic for me to discuss. I’ve spent the last ten years grappling with it. It is quite something to confront your mortality at 19 years old. At that age, you don’t have enough experience in life yet to understand how tremendously wasteful it is to die so young. You don’t know how much you’re going to miss out on, not specifically at least. I don’t think any of us do except in hindsight. We only know that there is still a tremendous amount of ill-defined ‘life’ left to be lived, but who even knows what that means.

The subjectivity of experiencing time is a funny thing. It is easy at that age to develop the mistaken impression that the rest of life’s long road is just more of what you’ve already seen: school, work, dating, late nights out, the occasional vacation to somewhere exotic, and the hopefully less-occasional heartbreak. I think that’s why death doesn’t seem like a big deal to a young man in the moment. Certainly, it didn’t for this young man at least. But ask anyone who’s been around for long enough: to not even consider the consequences is what passes for bravery when you’re young.

Death Comes Quietly

Let’s wind it back a little and set the scene. I nearly died when I was serving in the Army. It wasn’t on the field of battle, it was in a hospital emergency department. It wasn’t cool. It wasn’t badass. It’s barely what I would call dignified. It definitely wouldn’t have made for a good movie.

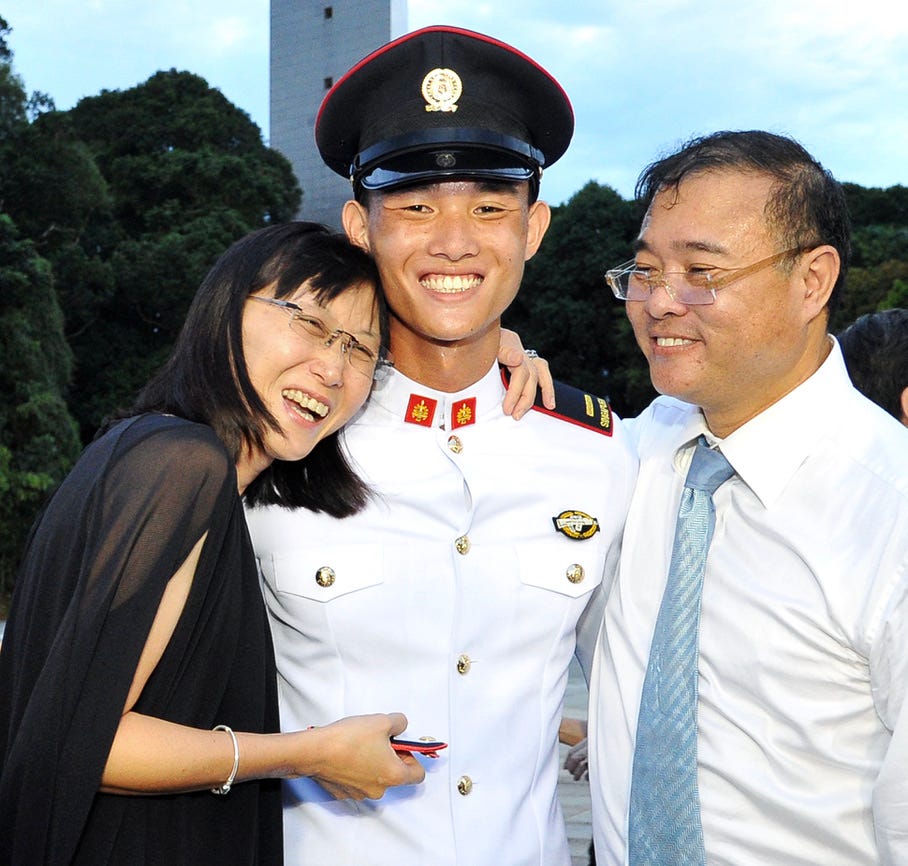

It happened during the early hours of October 21st 2014, the day after I’d been inducted into the 97th Officer Cadet Course. I was up and in formation by 0500 for PT. After the first jumping jack, my chest hurt like hell. I thought I was having a heart attack.

But I told myself to stop being a little bitch and to keep going.

All I’d ever wanted was to be standing there, sweating in the early morning darkness, serving my country. I busted my ass all through Basic just for the chance to attend Officer Cadet School, the “Premier Institution of the Singapore Armed Forces.” I was walking in my Dad’s footsteps. I wasn’t going to fall out over a little physical discomfort on my second day.

The pain got worse as we started the two mile run. It was sharp, like a ball of spikes nestled under my collar, stabbing pain radiating and turning to electric fire racing from my chest out into my arms and into my back. It felt like some tremendous beast was squeezing my rib cage in its grip a little tighter with each step.

By the end of the run, I was wheezing and gasping for air, ready to keel over. I couldn’t feel my left arm. My chest had seized up. But the rest of my platoon was doubled over heaving too. My platoon commander, a wiry Dutch-Singaporean Captain, screamed at us to stand straight. We were officer cadets, not fucking recruits, and we should carry ourselves like it. I could barely breathe but I sprang upright. He was right. I was proud to be there and I wanted to be worthy of the title.

It took me 3 more days after that to actually give in and seek medical attention. Stupid me, I still thought it was some kind of muscular injury. I tried everything – stretching, painkillers, medicated patches. Nothing helped. The pain just kept getting worse.

The base Medical Officer didn’t know what was wrong and sent me to the hospital. As I waited in the Emergency room for the results of a chest X-ray, I started feeling a little embarrassed that I’d made such a big deal out of the whole thing. I was pretty sure I was fine. For a moment, I even convinced myself that the pain had subsided. I texted the Duty Instructor that I would be back in time for evening PT.

A nurse came out into the waiting area and asked me to follow her. She explained that they needed to ward me immediately and put me on high-flow oxygen. I thought it was just a precaution. Even as I put on the hospital robes and they strapped the oxygen mask to my face, I was still confident that I’d be back on base in time for dinner.

A doctor came out and said that an air bubble had ‘appeared’ inside my chest, and it was pressing on my lung. He assured me there was nothing to worry about, and that I should just call my parents to let them know. So I did, and I specifically said that I was fine, nothing was wrong, and that they shouldn’t worry. Of course they worried anyway, because that’s what parents do and I’m their only child, so my mom left work and came to the hospital.

After she arrived, that same doctor came back and gave us a slightly different account: he explained that I had suffered a ‘Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax’. My left lung had ruptured and was now collapsing, leaking air out into my chest cavity. It was getting worse with every breath I took, with the tissue now starting to wrap around my heart.

With each inhale, I was essentially killing myself.

They were warding me because it wasn’t going to resolve by itself, and if the oxygen mask didn’t work, they’d have to cut my chest open to staple my lung to my chest wall to prevent it from collapsing further.

Yeah, as you can tell, the doctor left out a few details the first time. He said he’d be back to check on me and walked back out as cheerfully as he’d entered, leaving my mom and I both there in stunned silence.

The next few days passed in a blur. I remember that we didn’t freak out, but once the initial shock wore off, it was replaced by a creeping dread. Time passes slowly when you’re staring at the ceiling of an Emergency Ward. It dawned on me that this might be it, that this might be something I can’t get out of, no matter how much luck or skill I had.

I’d nearly died twice before at that point: the first time while shoving a friend out of the way of a car about to run us down, and the second time while almost getting swept away at sea while scuba diving. On both those occasions, I acted before I had the time to really think about what was happening, and that quickness of action was what got me out of it.

This time, however, wasn’t something I could save myself from, no matter how fast or strong or determined I was. I was helpless. And slowly, the terror of that helplessness dawned on me.

My parents stayed with me the whole time. As you may know, I didn’t die. The oxygen worked within the first 24 hours and I narrowly avoided surgery. To the credit of my initial reluctance to seek help, I had actually managed to re-inflate my own lung slightly during the 3 days I took to see the Medical Officer.

Pressure Forward

I stayed in the hospital for another few days. As soon as I was discharged, I reported back to the base Medical Officer, who promptly downgraded my medical status and dropped me from the officer course. He told me that Army guidelines left him no choice, that I had a 20% chance of my lung collapsing again within 12 months (at which point open-chest surgery would be unavoidable). He said that I should just take the exit. That I’d done my part, no one could question that, and I should just walk away glad to still be breathing.

I did not just walk away. I got my medical status re-upped, and I eventually rejoined OCS to commission as an Army officer 15 months later. The subsequent odyssey I endured to do all of that is a story for another day (and it’s a good one too). But you might ask, why did I do that? Why did I put myself at great risk again? Why would I put my parents through that?

Was I stupid, reckless, brave? Was I a gloryhound? Was it love of country or lust for rank? Was I just a sucker for pain?

I’ve been asking myself that for the last ten years too. Every day since has felt borrowed, because there are plenty of good reasons why I shouldn’t still be here. And with the perspective of having made it all this way, I now have an alternative explanation for what drove me to step forward again.

That day, ten years ago, I was afforded another chance at life, not as a gift but as a loan. One day, however near or distant, the Reaper would be back to collect.

Man is uniquely cursed with knowledge of his own mortality. We are the only species conscious that the passage of every second pulls us closer to the grave.

But we do not face that knowledge with despair. On the contrary, it creates something inside us that compels us forward – some instinctual truth that tells us that the purpose of life is to put it all on the line, and to push for more. I said earlier that it’s easy to develop the impression that the rest of life is just more of the same of what’s come before. That’s true, it can be. It’s easy to sleepwalk through life if you aren’t careful.

I refused to. Even though I wasn’t aware of that enough to articulate it at the time, I knew that to walk away at that moment would have meant a surrender. And I could not stand the idea that, with the little time I had left, I would squander it on more of the same unremarkable life that I had before. I wanted more. I chose to chase after more. And that choice set me on the wild path that I walk today.

I believe we have the lives we deserve. We are not owed anything. Reality does not naturally care about whether we live or die. But here’s a nifty secret of life: with the limited time, resources, and energy we have, we still have the power to make reality care.

More than that, we have the obligation to make it care about our existences. We make it care by serving those around us, by striving, by building great things, by loving and feeling and making our presences memorable.

Play it fucking loud

You’ve been told to simply make a difference. I am telling you that is insufficient, that differences do not inherently matter. The world will be different but for you regardless. We make choices every day that fork reality. A beetle landing on a leaf could be black or brown, but it won’t matter an ounce to the bird that eats it.

Those other universes in which you are gone could be barely different. Or they could be gulfs apart. You have the ability to shape how vast that difference is by the strength of your actions today. Expand the radius of your life. Make the difference matter. Make those other realities worse by virtue of this present one being better.

It is our moral responsibility to make that difference matter. I know it is, because it will not happen naturally independent of our actions.

None of us are preordained for greatness. None of us matter except for what we do – for what we choose to do, and how we choose to live. You can believe in destiny, in fate, in inevitability. I don’t. Life is optional, as is our participation in it. Every day requires a conscious choice to stand up, shoulder the burden of living, and continue walking forward down our respective paths.

If all of life, all of us, are optional, then make this option exceptional.

We can float through life gossamer as spider’s silk, barely affecting the present state of nature and leaving no trace of our passing. Or we can rock up, kick down the fucking door, and carve our names into the stone of history. Do not go gentle. Demand to be remembered, and give both body and force to that demand with your actions.

Legacy is the other word for this: to leave behind something great worth remembering, and to impact those around us such that we are deserving of remembrance.

Camus said one must imagine Sisyphus happy. That life means nothing save the meaning we ascribe to it. We struggle because we choose to – that part I agree with. But I think life has a meaning of its own.

The meaning of life is this wonderful choice we have, the choice to make this reality so bright that all others dim in contrast. Only the dead have been stripped of that choice. Their forks stop when they do. I like to think that, ten years ago, something in me knew this truth and declared in the quiet of my mind that I was not dead yet, and that I hadn’t done everything that I could, that I hadn’t been all that I could be.

And if every day was now borrowed, it was my duty to do everything in my power to make sure that my difference mattered before the time finally came to pay back my debt.

An abundance of time blurs the mind. The opposite sharpens and narrows your focus. I have a perpetual ticking clock hanging above me.

So do you.

Have you noticed it yet?

Understand This: One Day, This Will End

This understanding has driven how I live, and every choice, every decision, every action I have made since. I am always conscious that my time is on loan, and that it is a privilege that I get to spend both it, as well as the time of those around me whom I love and treasure.

I’ve been asked before why I place such a massive emphasis on my military service. Every man in Singapore does it, so why make a big deal out of it?

Well, this has been my account of why. Because I nearly died. Because it wasn’t a split-second near-miss, but a slow and drawn out affair that made me stare down the possibility that I would not be going home. And because coming that close to death helped me to understand the dual-truth that we have less time than we hope, but so much more control over how we spend it than we might think.

I feel like I have earned the right to be conspicuously proud of my service, and of my willingness to stand resolutely when my number was called. After all, the doctors told me I had a 20% chance of my lung collapsing again and killing me (40% if I chose to pick up smoking, which to date I never have). And still I volunteered to serve to my fullest ability.

But moreover, I take great pride that when presented with that easy out, I had the steeliness of spirit and clarity of vision to understand the true magnitude of the consequences of choosing poorly: something inside me told me that if I lay down my burdens and walked away, if I let myself down there, I would be surrendering not just my honor, my hope, but I’d be surrendering the spark that lives in all of us that inspires us to do more, to strive. And I would never be able to look myself in the eye again.

I was told there was a good chance I might die, after I already nearly did. And I came to the understanding, by myself, that it was okay. I did not yield. I took those odds in hand, and strode forth to build a life.

Bonus Rounds

Looking back on all the things I’ve done, friends and family I’ve loved, lives I’ve touched in these past ten years. I think I can say I have made good use of my borrowed time.

Every day, I wake up and try to remember that today could be the day that the Reaper calls on me again. But this isn’t always easy, and I am flawed. On many days, I forget and I fool myself into thinking I’ll live forever, so it is okay to waste precious moments. And I think it’s because this is no Sword of Damocles. This is not a lingering threat, but a universal constant that fades into the background with ease.

As Marcus Aurelius said, “everything was born to die.”

This is as true for you as it is for me.

We are destined only to do one thing: to run out of time. There is never enough of it. It doesn’t belong to us anyway. It runs forward unfalteringly despite our best efforts to cling onto it.

The tide does not heed our cries to stem it.

There will always be more birthdays, graduations, and weddings. Always more celebrations than we will be able to attend. And for that matter, also more funerals, more tragedies, more tears. And that is just how it is.

There is more joy and pain in this world than we are able to absorb.

All we can really do is play as many hands as we can, as fast as we can, and take as much of it – good and bad – off the table as possible so that when the buzzer eventually sounds and we are forced to step off the field, we can do so knowing that they’ll miss us.

Yes, I’m saying that life is just a series of gambles. It’s a smash-and-grab job.

And the prize?

The prize is that we get to do any of it at all.

Love it!